Written by Iram Sammar

Date: Dhu al-Qidah 22, 1446 AH (May 20, 2025)

(The Hijri date today is Tuesday, 22 Dhu al-Qidah 1446 in the Islamic calendar. Using the Gregorian calendar, the date is May 20, 2025)

One of my favourite topics to teach at Key Stage 4 (or GCSE) has been Distinctive Landscapes. Whilst many colleagues found this quite tricky, and as one colleague put it, “I prefer the students to experience a landscape,” I would use this as an escape from the urban strain.

How a trip to Sheffield led me to explore the Peak District

SHARE invited me to speak at their amazing conference “Revealing hidden histories and geographies of empire: what demands should we make of our education system?’ Speakers included Abtisam Mohamed – MP for Sheffield Central, Alan Lester – Professor of Historical Georgraphy, University of Sussex, myself, and Sheffield Museums, Roots & Futures and Sheffield Anti-Racist Education. A blog in itself to come on this. After the event, I treated my family to a “walking trip” to the Peak District. Surprisingly, I had never been before.

Sheffield, in itself is a city known for its industrial roots and creative energy, and it sits right on the edge of a UK landscape treasure—the Peak District. We had the car, so the national park was just a short drive away. My children did not know what they were going to experience, so it would have been almost criminal not to escape the concrete and lose ourselves in the wild beauty of the hills. If you’re a student looking for a weekend walk, an urban dweller needing a breather, or just visiting the Steel City, the Peaks are a must, so get your hiking boots on!

Throughout my journey studying geography, I have felt the countryside to be a “white space”—a place imagined and experienced as predominantly white, rural, idyllic and often exclusionary. All those wasted years, I saw the rolling hills and quiet lanes, a place to speak a language of a certain kind of “belonging” that couldn’t speak to me. But that’s beginning to shift. Across national parks, including the Peak District, a pleasant array of diversity is visible, more Black and Global Majority presence, lot’s of young urban explorers, and diverse communities are enjoying these magnificent spaces within these landscapes. From grassroots walking groups to inclusive outdoor festivals, the countryside is slowly becoming more representative of the nation it surrounds—proof that the outdoors defies exclusion as it belongs to no one, but everyone. Many walkers would stop and say, “Hi, not much longer to the wonderful view over by the giant rocks.”

As Abtisam strongly stated, we are not “an island of strangers,” rather:

“We are a mosaic of neighbours, friends and families from across the world. We all cooperate and contribute to our community. Our country was rebuilt from the contribution of successive generations of migrants, like my grandfather and father who worked tirelessly in the steel industry. They were not strangers, but part of a city and country that welcomed them.”

It is important to hold space and celebrate the true meaning of community in its diversity and inclusion, where difference is seen as a way of knowing and getting to know one another.

Ladybower Reservoir

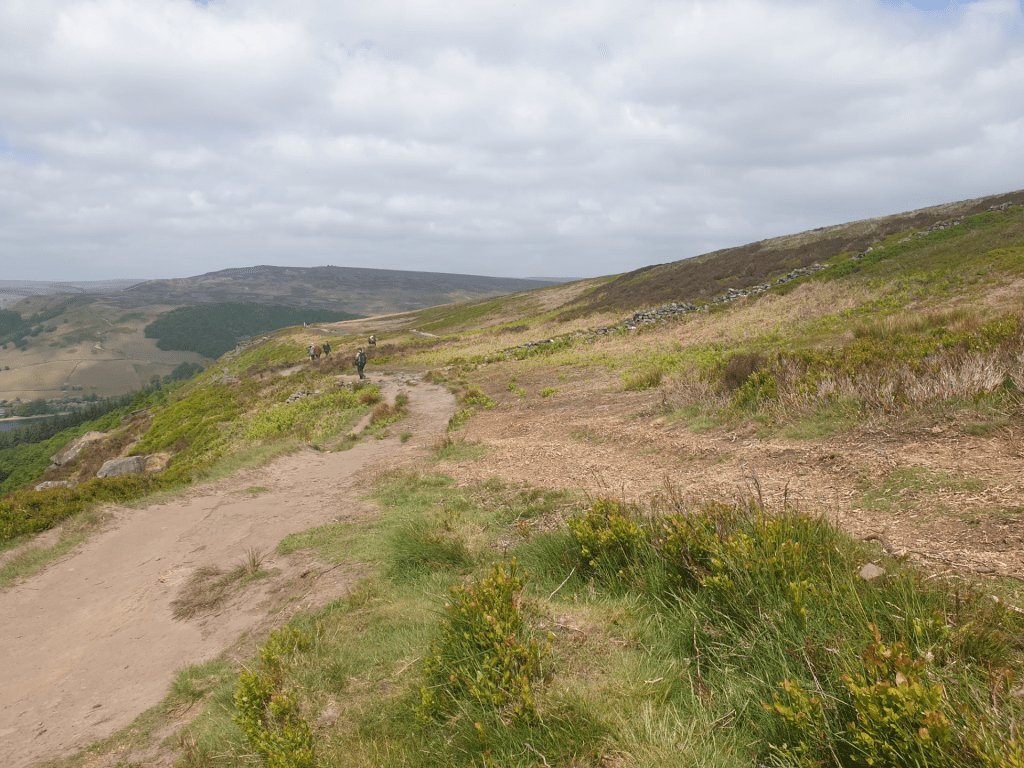

Walking up to get an ultimate view of Ladybower Reservoir was something quite of an adventure. After a lot of scrambling and tripping up over loose rocks, we made it – of course I was the last in the family to reach the viewpoint above Ladybower Reservoir. There are fresh natural springs, streams, and trickling water sources on walks in the Peak District, especially where we went. The area is rich in natural features due to its geology—particularly in the White Peak (limestone country), where underground water systems often surface as springs. We only had time to visit Ladybower Reservoir, so you can definitely encounter springs, streams, and flowing water, especially if you take one of the more elevated or woodland routes. The whole area is part of a scenic, lush, upland catchment, where water flows naturally through the hills, especially after rain. This stunning walk takes you through areas with natural springs and upland streams, particularly as you go down toward Rowlee Pasture, or cross through moorland areas. It’s a tough route, but water is often visibly bubbling up in places where you find lots of peat and mossy ground. As you head uphill from Ladybower toward the rocky escarpments of Derwent Edge, you won’t find large springs, but there are smaller streams fed by moorland runoff. A lot of this is seasonal, so dependent on rainfall.

It wasn’t easy, let me tell you—it was steep, uneven, and seemed to go on longer than expected! I kept soldiering on, regardless of the wind picking up speed and trying to topple me over. An amazing path is carved out conveniently for the hikers, where there are parts extremely narrow near the top. Your legs will burn, your conversations will fade into gasping silences. One thing is for sure, the oxygen your lungs will inhale will keep you motivated to keep on going. Fresh air. Many times, you will think to yourself, “turn back, you’ve seen enough beauty.” But then, you will meet a couple, or some friendly hiker walking their dog, encouraging you to keep going. When all of a sudden, “Oh, SubhanAllah”, the trees will clear, and there you will see it: Ladybower stretching out like a shimmering mirror, reflecting the beautiful sky in its surface, embraced by breathtaking rolling hills of the Peak District. “Ma’ Sha Allah,” it was worth it, but as I write this, my legs and feet are still killing me! I promise the exhaustion will melt into awe. This struggle gave the view something beyond beautiful, it felt like winning a medal, where nature cheers you on, and the rocks stay still in their silent caress. On our walk back down, there was an opportunity to pray Zhur salah, which is the midday Islamic prayer. Therein, hidden within the veil of the woods, was the perfect surrounding to attain Khushu (attentiveness and tranquility in prayer). Praying in the outdoors has its own sense of serenity. We drove home with contentment and inner peace (sorry for sounding like the Kung Fu Panda!).

Enough of the poetry, let’s get into the geography. When describing landscapes, I quite like getting the students to use the diagram from OCR GCSE (9-1)Geography B: Enquiry Minds (Figure 6, Rogers 2020, et al. p. 63). It shows the many different elements that make up a landscape. When you get your students to a location such as the Peak District, get your students to close their eyes and recall what they saw walking up and in front of them. They can discuss which elements they can see using the landscape wheel below.

How can we read the landscape?

“An important part of any landscape is the shape and height of the surface landforms that can be seen. A landform can be defined as ‘any physical feature of the Earth’s surface which has a characteristic, recognisable shape and is produced by natural causes’. Landforms help provide the overall character of a landscape, as well as affecting its soils and climate and the ways in which people use it.”

Coles, Jo; Payne, Jo; Parkinson, Alan; Ross, Simon; Rogers, David. OCR GCSE (9-1) Geography B Second Edition (Ocr Gcse 9-1) (p. 182). Hachette Learning. Kindle Edition.

Next time, perhaps you can get your students to write a blog on their physical geography field trip. I would love to hear about it. Personal experiences, like the ones I have shared with you, get you thinking about landscapes in rich and meaningful ways. Bringing out the geography is sometimes difficult in words, but using some phrases you say during the trip and recording these gives a sense of place to the reader. Those initial feelings and words that come out embody the whole experience.

What physical landscapes of the UK have you visited?

Where would you like to go?

One for me: Where do you think I should visit next?

I hope you have enjoyed reading this as much as I have enjoyed the writing. Thank you and, until we meet again, PEACE.