Geographies of Creativity / Creative Geographies

Written by Iram Sammar

Date: Rabbi 1 26, 1447 AH (18 September 2025)

The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers) Annual International Conference 2025, chaired by Professor Patricia Noxolo was held at the University of Birmingham and online from Tuesday 26 August to Friday 29 August 2025, on the theme Geographies of Creativity / Creative Geographies. The conference was an incredible experience for me personally, opening spaces where participants could share not only their research but also the inner feelings of joy and distress tied to marginalisation, race, and the lived realities of ‘being’ othered and reclaiming identity. Creativity and the geographies aligned were embedded within the conference, from global music, culture and art to spirituality – including Qur’an recitation. In my case, being Muslim and racialised by the mainstream discipline of geography, I do not find it easy to show up visibly in predominantly white spaces. It was a refreshing surprise to feel the love and warmth of those involved in the organising, presenting, and observing of this year’s conference.

One of the most powerful moments of the conference for me was in collaboration with the RACE working group of the Royal Geographical Society. This group marked its 10th anniversary this year with a pre-conference gathering, The Azeezat Johnson Memorial RACE Pre-Conference Event 2025 that, as always, created space for postgraduate and early career researchers to connect and share their journeys. I am a relatively new member and postgraduate representative alongside Charden Pouo Moutsouka. What stood out was how the conversations stretched beyond the well-worn idea of the “leaky pipeline” to address the fuller spectrum of Black and Brown student experiences, career trajectories, and the intersections of academic work with community activism. We welcomed two exceptional researchers, Dr Lyn Kouadio postdoctoral reader at Oxford University, and Saffron Powell PhD candidate at King’s College London, to share knowledge on their research, respectively. Saffron shared elements of her research and talked about how current teacher education policy fails to support initial teacher education providers in developing antiracist teachers. She spoke about how such educators can empower all students and prepare them for a ‘diverse and multicultural world,’ whilst providing meaningful education for racially minoritised students and colleagues. Lyn, who is a Beacon Junior Research Fellow in Postcolonial and Race Studies, shared her research on transnational justice through the politics of epistemic (in)justice in (post)colonial Black (Francophone) Africa. Her current project research focuses on colonial archives in broader repatriation and reparations debates in international politics (see link). Karina Kanda, Azura Farrell-McLeod, and Obinna Iwuji in their presentations, shared beautiful poetry and reflections on their amazing research.

What stuck with me and everyone in the room was Anita Shervington’s concept of cultivating community-rich projects so beautiful flowers can grow for us to harvest. Those flowers are a metaphor, seen as the final product of the hard work that Black and Global Majority people put in, so communities can flourish. Anita spoke about BLAST, a pop-up festival and engagement platform that brings together ‘the power of science, arts, and Black culture to drive social, economic, and environmental change’ (see link). She works as a Birmingham-based community engagement strategist. She reminded us in the room, how the work we do as Black and Brown people can be seen as cultivation, and that we therefore must not just let institutions and extractivists harvest our flowers. I am not sure if I have conveyed with the same eloquence as Anita, but I hope this resonates with people working hard to decolonise and work through anti-racism praxis.

These discussions resonated strongly with my own commitments and align with the powerful interventions of scholars like Dr Azeezat Johnson إِنَّا لِلَّٰهِ وَإِنَّا إِلَيْهِ رَاجِعُون, whose work continually urges geography to take seriously race, embodiment, and the everyday politics of belonging. Our sister, Azeezat ‘brought a deeper meaning to the discussions around the geographies experienced by Black Muslim women,’ (quote from a blog). The event closed with a collective reflection on the future of the RACE group itself: questions of whether and how the group should continue, what members now need from it, and how its vision might evolve to meet the challenges of the next decade. I must say the halal cuisine and variety of condiments were impressive, all enhanced by the fact that this event was hosted at Ikon Gallery, Birmingham. Love, respect and care were at the heart of the event.

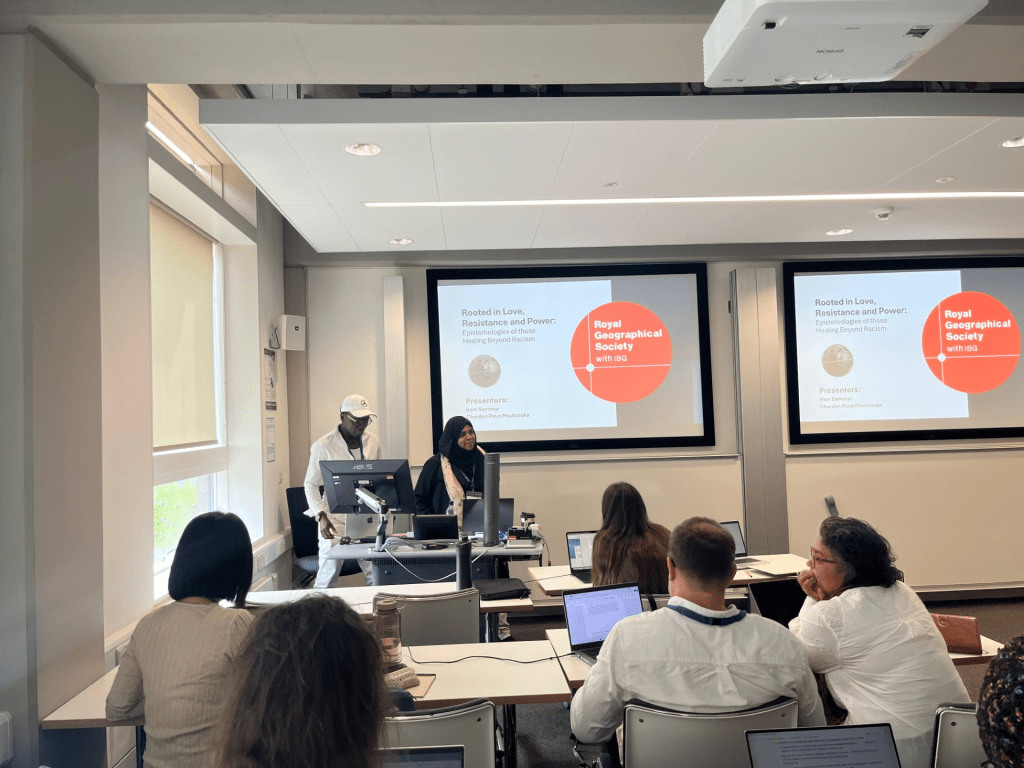

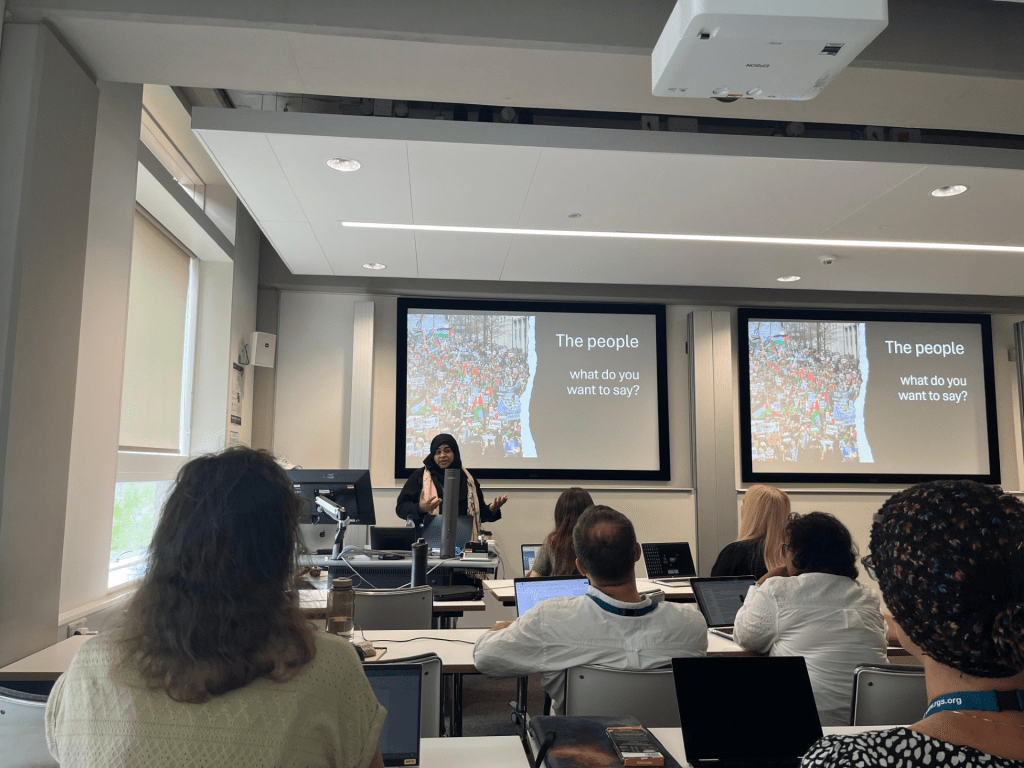

The following day, another powerful moment came through a session I presented in collaboration with Charden Pouo Moutsouka (University of Oxford). We summoned critical and creative engagements with love, resistance, and power as central themes for reimagining geographies. Our paper foregrounded the often lost or erased epistemologies of communities that have endured racism(s) within their geographical imaginations and lived realities. Our audience was blessed to be in the company of Professor James Esson, where emotion and depth of understanding, and being uncomfortable at times, made space for critical reflections.

Our reflections drew deeply from Black, diasporic, Indigenous, and Global Majority epistemologies, tracing how these knowledge systems embody expansive practices of love and resistance, and how they reclaim sovereignty in the face of racial violence past and present. The session did not simply diagnose oppression; it opened pathways toward collective healing. A guiding question echoed through the room: How can we draw on our own cultural, spiritual, and embodied ways of knowing — rooted in love, resistance, and power — to heal from the ongoing wounds of racism?

This was beyond a call for incremental reform; it was the possibility of a paradigm shift within geography itself. A shift away from frameworks that reduce resistance to what is only ever portrayed through Western epistemologies, and toward centering Black, Indigenous, diasporic, and decolonial knowledge systems. The paper looked to bell hooks and el-Hajj Malik el-Shabazz (Malcolm X) to illuminate how storytelling, song, poetry, art, and prayer serve not just as cultural expressions but as sites of epistemic resistance. From the mothers’ sigh to the sanctity of the home, from pilgrimages to spaces of spirituality. We invited our audience to see how love itself could be understood as a decolonial method. Critically, the paper also urges us to confront the damage left by coloniality and the ongoing failures of Western epistemologies to embrace plurality, especially when grappling with racial trauma and healing. It called for rethinking geographical landscapes not through the tired dualism of “over here” versus “over there,” but through an understanding that the wider world lives, breathes, and resists as one. Watch this space for our journal article, In Sha Allah.

Close to my heart was participating in the Pedagogy Café: Teaching and Learning (from) the Middle East and North Africa. A devoted team of scholars facilitated this heartfelt session: Professor Aya Nassar (Convenor, Discussant, Panel Chair Durham University) and Dr Muna Dajani (Convenor, Discussant, Panel Chair, London School of Economics), Dr Sasha Engelmann, Royal Holloway, University of London, Dr Dena Qaddumi, London School of Economics, and Dr Olivia Mason, Newcastle (Discussants). The Pedagogy Café created a collaborative space to explore the creative energies that had been shaping how scholars and educators taught and learned about the Middle East and North Africa. It resonated with the conference theme by foregrounding innovative pedagogical practices, liberatory curricula, and alternative geographies of knowledge that were being imagined and enacted in classrooms, communities, and online spaces.

Over the past year leading up to the conference, a renewed energy had circulated among scholars, educators, and activists committed to teaching and learning about the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). Palestinian spaces and circles, in particular, had been at the forefront of building free, critical, and liberatory curricula that resisted silencing and reimagined the academy’s relationship to the region. Inspired by these efforts, the Café convened a space to come together, share, and reflect on creative approaches to teaching and learning from and about the MENA region.

The initiative emerged from a moment of both urgency and possibility. On one hand, the increased demand for pedagogical resources highlights the difficulties many face when teaching geographies of the Middle East — difficulties amplified by political silencing, disciplinary gatekeeping, and structural inequalities within higher education. On the other hand, the imaginative work of educators and their allies had opened new pathways for curricula that were free, collaborative, and transformative. I hope to bring such discussions to the GA annual conference in 2026.

At the Café, we also held space for these ongoing pedagogical endeavors: showcasing how the geographies of Palestine have been affected by the ongoing genocide and scholasticide the whole world is witnessing – reflecting on the processes behind them, and reimagining their potential for reshaping geographical teaching and learning through criticality. Through short roundtable pitches, invited speakers introduced initiatives they had been part of — from online syllabi and open readers to community-based teaching projects. The conversation then opened up, creating room for collective discussion, troubleshooting challenges, and asking difficult questions about what it means to teach and learn MENA geographies today.

In foregrounding critical questions, the Pedagogy Café reflected not only on teaching practices in the moment but also on the connections between past and present struggles, and the possibilities for pedagogical futures centered on liberation, collaboration, and accountability. Ultimately, the Café offered an invitation to reflect on how we teach, to learn from one another, and to push beyond disciplinary confines toward more expansive geographies of knowledge.

These spaces are not without spontaneity, as Dr Gunjan Sondhi and Professor Parvati Raghuram in their session: Rethinking categories under attack: Creating responses, asked me to speak on the geographies of Palestine in the school context. Always ready to talk and share my thoughts, here I was given the space to speak freely with no inhibition or fear of being silenced. Gunjan talked about ‘confusing times’ and navigating how to rethink our categories and make them more expansive (Sondhi 2025) – whilst working to decolonise them. The presentations reflected on confronting ‘an intensification of the opposite, the pressure to erase categories that focus on power relations – migranticised, classed, raced, gendered, Anti-Seminitism and Islamophobia.’ The panel was captivating and focused on the challenge to inclusivity and expansiveness that are faced in the ‘contemporary conjuncture.’ They asked the following questions: Do we hide and smuggle those categories, abandon them, or confront the pressure to erase them? What does geography with its overarching concepts, such as space, time, environment, and landscape, offer us when rethinking categories? Again, I was left wanting to carry on listening to speakers, such as Angela Last, Agostinho Pinnock, Lea Haack and Jennifer Veilleux. We had a tremendous audience with great scholars who have influenced my own work, such as Tariq Jazeel.

As the conference came to an end, I attended a session convened by Dr Rita Gayle and Dr Colin Lorne. Rita posed some intriguing questions to get the audience engaged in a roundtable discussion to reflect on the possibilities of thinking with the archives of Stuart Hall and Doreen Massey ‘to help interpret and intervene in the troubling present.’ It was a mind-blowing session, where the whole theatre was engaged in breaking the silence and speaking up and to each other. We were asked to rethink how Stuart Hall and Doreen Massey’s work can be understood today, especially with some of the troubling far-right sentiments against immigration and marginalised communities, and the national rallies that were brewing during the time of the conference. There was a discussion on what the St George’s flags were symbolizing and how this impacted different communities living in Britain today. I had an interesting conversation with the Uber driver just before the session, who is local to Birmingham. He talked about how hard his father worked in the region in the 1970s and the difficulties he endured making a home in Birmingham. Due to anonymity, I won’t mention his name, but his heritage is Muslim Pakistani. One of his main concerns was the anti-Muslim and anti-migrant feelings amongst the far-right organisations and supporters. He said: ‘my main concern is getting people safely home or to places in and around Birmingham, so when they say we are dangerous (Muslim men), it makes me upset – we are the ones making sure people are safe at God-knows what hours at night! People coming back from clubs and people not knowing the place well – we are there to help.’

Like the friendly Uber driver mentioned, the meaning of the St George’s flags going up for my own Pakistani heritage parents during the 1970s and 1980s, was entrenched within racism and a sense of being ‘othered’ and often excluded (see blog). Driving in and out of Birmingham came with a visual display of patriotism and a clear message of incitement of community division. I am British-born – is this my flag too? My own son asked me: ‘Is England playing in a football tournament?’ Do I explain, or just let him innocently think of a possible brighter future, where your skin tone, religion, place of heritage, or migration status won’t define your belonging or existence? The session definitely kept alive the thinking with Hall and Massey about ‘what’s politically at stake today: not to find easy answers to the questions thrown up in the here and now, but to help think the many times and spaces of current conjuncture in all their complexity.’ Both these scholars operated as everyday people with everyday communities, whilst writing for the institution and speaking to power. Rita was engaging and taught us what it means to never forget our scholars who paved the way for us, newer scholars.

I could write more, and probably should, but for now, I hope you have enjoyed some of my reflections. There were a few nice places to pray in Birmingham University, which is always nice (see image below). A special heartfelt thank you and prayer goes out to Professor Pat Noxolo, for creating a space where we all came together and shared knowledge and ideas – felt seen, loved, and respected. Thank you for reading, and please do get in touch if you want to connect.

Oh, and I almost forgot – the edible cups. Have a bite!